Entering into a discussion on hope, and hopes, via some thinking about the therapy approach I specialise in for my day job – solution-focused practice.

In Five Go Mad In Dorset, broadcast on the first night of Channel 4 on 2nd November 1982, Dick of the Famous Five, keen to know what was happening, exhorted one of the other characters to:

“Come on, tell us everything at once. We must know, because there’s something very peculiar going on, that’s for sure.“

Having created a blog to share some thinking and learning about hope, a considerable time after I set about engaging in this, I do have a sense that I want to write everything down, all at once, so it’s hard to know where to begin.

However, I’m fairly sure that my interest in hope originated from my work as a solution-focused practitioner, so this post will focus on aspects of that approach. I’m going to try not to assume any prior knowledge of solution-focused practice on the part of the reader, so those of you who are well-acquainted with it, please bear with me any time I enter explaining mode.

One of the main things I want to convey in this post is a confusion that I believe surrounds the notion of hope, and how such a confusion can manifest itself in the particular case of solution-focused practice, but which I think is widely generalisable. In recent years I have taken to describing solution-focused practice as a hope-oriented, hope-focused or hope-centred approach, and this in itself might have served to add to the confusion, or has arisen from my own confusion, or both. I’m not referring to the different endings to that adjective, but to the use of the word hope at the beginning of it. One way of addressing this would be to add an s, turn hope into hopes, as we shall see.

Another question that is interesting me now is whether solution-focused practice has always been a hopes-focused approach, even before the word hope was explicitly used by its proponents. I don’t recall any mention of hope on the first training course I attended, on “solution-focused brief therapy” (SFBT), 30 years ago. I was working as a social worker at the time and looking for something to help me in the therapeutic aspects of my role. SFBT was a therapeutic approach that had already by then spread beyond the world of psychotherapy and counselling, and into many other helping professions whose practitioners talked with their clients to help change to happen. By the end of the course it was clear to me that I could use the approach in my job as a social worker, but it took some thinking to work out ways in which to do this.

A difficulty in applying it in social work was that the starting point of solution-focused practice – at least the version of it I learned in 1995 – was to ask what the client wanted, and social workers frequently have to be led by their statutory duties to help and protect, rather than by the wishes of the client. I’ll leave social workers and their difficulties for now though, as I want to explore this opening solution-focused question, of what the client wants. There was much experimenting with ways of asking this question, throughout the 1990s, in order to make it clear, for the therapists as much as for the clients. The question is aimed at eliciting a desired outcome, yet other desires can be heard in it, such as, what do you want us to talk about, or what do you want me to do for you? The wording of the opening question I learned to begin with was: What needs to happen for this to be useful for you?

A few years after my first course, the therapist and trainer who ran it, Chris Iveson, asked a client what she hoped for from the session, and shortly after asked another client: “What’s your best hope from this meeting?” With an ’s’ added to hope, the question became what is now known as “the best hopes question”, which has become famous throughout the solution-focused world: What are your best hopes from our work together?

As my trainers and mentors at BRIEF – the London centre for solution-focused practice founded by Chris and his colleagues – began routinely asking this question, I happily followed suit, and I don’t recall thinking much about it until some years later, by which time I was working at BRIEF myself. I was then involved in a couple of presentations about “the best hopes question”, which played a part in promulgating it, especially the second one, in 2008, at the annual SFBT conference in the US.

Solution-focused practitioners talk a lot about the questions they ask, and are prone to giving questions names, like the best hopes question, the miracle question, the tomorrow question, scaling questions and so on. I have reservations about this, partly as it tends to centre the practitioner and their questions, rather than the client and their answers. However, the introduction of the idea of asking clients about their hopes from the work at its outset has played an important part in the development of the approach in the last 25 years. It has also contributed to the confusion I referred to earlier.

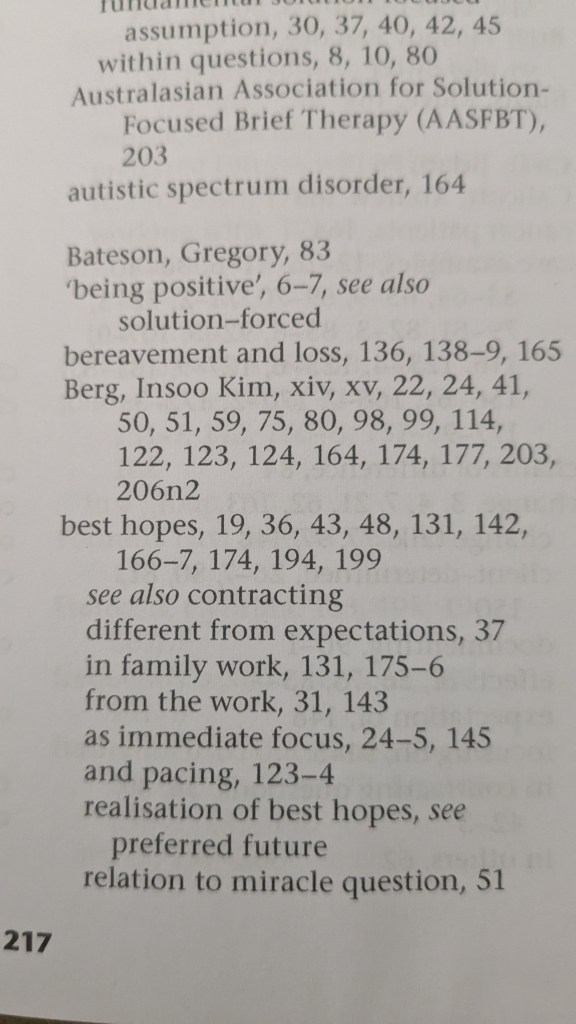

As I prepared for the keynote I was to give at the UK Association for Solution Focused Practice conference, mentioned in my previous post, on solution-focused practice and hope(s), I wondered if hope had been explicitly mentioned in early SFBT texts, and leafing through their indexes suggested not very often. When reading an article called Hope: Research and Theory in Relation to Solution-Focused Practice and Training, I discovered that its authors had had the same idea (Blundo, Bolton and Hall, 2014). I was surprised to see that the index of my book on solution-focused practice, also published in 2014, was one of those they had scoured, to find no mention of hope. I checked and found that they were right.

However, there under B were “best hopes”. It seems that we solution-focused practitioners cannot talk about hopes without the word “best” attached! A second edition of my book came out 5 years later, and at least then I thought to add something in the index under H. It wasn’t hope though, but hopes.

In my previous post, I referred to a distinction made by the anthropologist, Stef Jansen (2016), between the transitive and intransitive modalities of hope. He had recognised that the meaning of the term and its status in its anthropological analysis were often left unspecified, including in his own writing. His distinction was an attempt “to initiate a move towards a degree of clarity”. What he called the intransitive modality was hope as a feeling – hopefulness. In its transitive modality, hope is seen as having an object, or objects. One hopes for something, or that something will happen. It can be seen that the transitive modality is how it is used in the question: What are your best hopes from our work together? And that the transitive modality appears in my book’s index, but not the intransitive.

Jansen also describes hope as a “relational phenomenon in historical time”, which fits with how it appears in the solution-focused “best hopes question”. This is about the client’s hopes from the therapy, as opposed to more general hopes. They are hopes that the client has in relation to the therapy. If we look again now at the question, it can be seen that it contains a very important assumption, which is that the client has hopes that something will come from the therapy. It seems to be a reasonable assumption to make, that if someone has come to see a therapist, then they must be hoping that something will come from this, something positive for them. They must have hopes – from the therapy. Note that this is not the same as saying that they are a hopeful person, or even that they are feeling hopeful that the therapy will help. The transitive does not imply the intransitive.

Not being clear about this distinction is one way that talking about hope can lead to confusion. This is why it makes sense to call solution-focused practice a hopes-oriented approach, rather than a hope-oriented approach. I won’t go into detail here about how solution-focused work develops beyond its opening question, but in summary, the client’s hopes remain the focus throughout, as the work as it continues will involve a mixture of future descriptions of the realisation of the client’s hopes and descriptions of times when this is already happening.

This continuing focus on the clients hopes is distinctive to solution-focused practice, in a way that hope in its intransitive meaning is not. Hope could have appeared in my index, alongside hopes, but only to the extent that it could appear in books on any type of therapy. Hope is one of the “common factors” that contribute to good outcomes across psychotherapy in general, irrespective of the model being used.

Confusing these different ways of thinking about hope has implications for how we see our role, not only within therapy, but in many other areas of activity. I was once invited to an event run by the Social Workers Union that focused on government austerity measures and how to respond to them, to speak about what a solution-focused approach to this might consist of. At one point, when the discussion became mired in the difficulties caused by governmental cuts, the chair turned to me and said, “You’re the hope man, can you give us some hope?!” I responded by saying that I didn’t need to give anyone there hope, as everyone had hopes already, otherwise we wouldn’t be there. I suggested that we focus on what we had noticed recently that gave us hope that it was worth coming together at an event like this to resist the austerity programme, and the discussion shifted to recent actions people had taken or witnessed.

One of the initiators of the solution-focused approach, the brilliant therapist, Insoo Kim Berg, wrote that “hope is the greatest gift we can offer our clients” (Berg and Dolan, 2001). While hope is crucial, we need to interpret these words with care. Insoo was also fond of quoting the Australian systemic therapists, Peter Cantwell and Sophie Holmes, who advocated the Zen-like “leading from one step behind”. By asking a client what their hopes are, we can ensure a focus on hope while being led by the client and their hopes. Seeing it as our role to inject hope could lead to an enforced positivity and we would be advised to pay heed to the words of another great therapist, Brian Cade. “It is important never to become more enthusiastic than the client”, he enjoined (Cade, 1998, 149), and, we can add, never to become more hopeful either.

References

Berg, I. K. & Dolan, Y. (2001). Tales of Solutions. New York: Norton.

Blundo, R. Bolton, K. & Hall, C. (2014). Hope: Research and Theory in Relation to Solution-Focused Practice and Training, International Journal of Solution-Focused Practices, 2 (2), 52-62.

Cade, B. (1998). Honesty is Still the Best Policy, Journal of Family Therapy, 20 (2), 143–152.

Cantwell, P. & Holmes, S. (1994). Social construction: A paradigm shift for systemic therapy and training, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 15(1), 17–26.

Jansen, S. (2016). For a Relational, Historical Ethnography of Hope: Indeterminacy and Determination in the Bosnian and Herzegovinian Meantime, History and Anthropology, 27(4), 447–464.

Leave a comment